Four years ago, my family began a tradition to honor our grandparents and family who has gone before us: raising the Armenian Flag at Fitchburg City Hall in honor of Armenian Genocide Remembrance Day (April 24). I did not anticipate how much this would mean to me emotionally, but I definitely felt emotion the first time we raised the flag when Stephen DiNatale was mayor, and again, felt tearful last year, when Sam Squailia was mayor. (We are raising the flag tomorrow, Thursday, April 24, at 1 p.m. at City Hall, 700 Main St., Fitchburg, followed by a brief reception with “Armenian Style” food — all invited!)

What does it mean to be descended from a people who have been regularly mass-murdered during so many periods of history? Many Armenian-American writers have grappled with this topic, starting with Michael J. Arlen’s, “Passage to Ararat” (1975). In that ground-breaking National Book Award-winning memoir, he told stories about his father, a genocide survivor and musical composer Michael Arlen, a man who basically refused to discuss his past. Arlen the son made a trip to Armenia, when it was still a Soviet bloc country and went back to the Old Country to attempt to reconcile — at least intellectually and emotionally — that question: “What does it mean to be Armenian?”

Often, reflecting on my heritage makes me feel somber. Earlier in the 20th century, there were around two million Armenians living in the Ottoman Empire in 1915; by 2022, 1.5 million had been murdered. That’s 75% of an already small population.

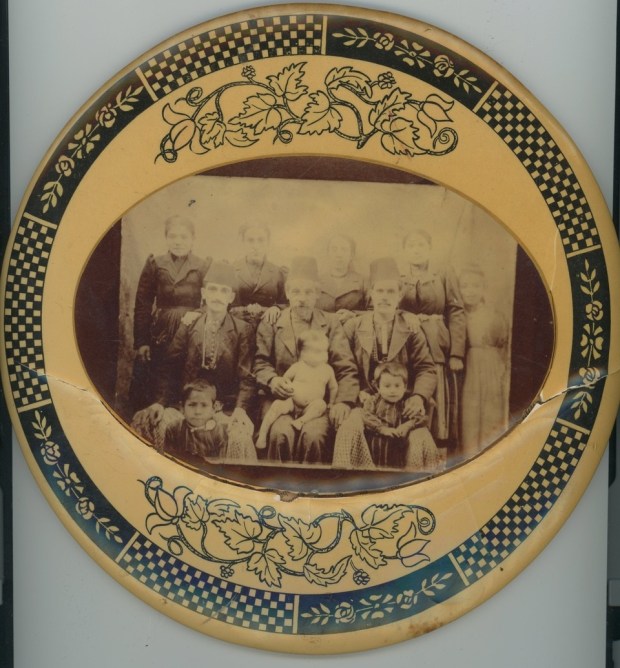

But some survived. My grandfather, Krikor Mirijanian did. Here is his story, from “The Uprooted,” Chapter 14 from Doris Kirkpatrick’s “Around the World in Fitchburg,” the history of global emigration to our city.

“Krikor Mirijanian had a hazardous life during his boyhood. The son of Bilbul and Krikor Mirijanian, he was born in Arapkir, near Harpoot in Turkish Armenia. During his boyhood the Armenian villagers were told to become Moslems or die. Only one person became a Moslem. The Turks drove the others on a three-month march during which most of them died. One day when there was an encounter with the Kurds everyone ran in a different direction. “That was when I lost my mother, my aunt, and my brothers,” said Krikor.

Hiding behind a rock, the small boy fell asleep. When he woke in the middle of the night, he found himself alone. For three days he walked, looking for a village. At last he found one and was taken in by an Arabian family.”

The next part of his story, I remember being told by Krikor himself, when I was a small child. The family had only daughters, and the father treated Krikor “like his own son,” he said. Krikor spent some time as a shepherd in the hills, but the man’s wife was increasingly nervous at their unwanted houseguest, because if the family had been caught harboring an Armenian, everyone would have been killed.

My grandfather had marks on his body, which he carried all his life. The first was a scar on his cheek — the Turks were in the habit of marking Armenians they meant to spare; usually boys young enough not to be dangerous and old enough to be enslaved labor.

But the second mark, Krikor made himself — a tattooed cross on the inside of his left arm, to show he was a Christian (Armenia was the first nation to adopt Christianity as a national religion, in 301 under St. Gregory the Illuminator.) You only saw the cross if his arms were loose. He made the cross with a needle and bonfire ash, so that when he was wandering in the wilderness, should he meet other Armenians, they could identify one another as Christians without saying a word.

The story continues in “Around the World in Fitchburg.” Somehow, Sarkis, my grandfather’s older brother survived, and found safe haven in an American orphanage in Urfa. Sarkis told the Arabs the British soldiers were in Urfa, and would come after the Arabs if they did not let Krikor go. The bluff worked and Krikor was allowed to leave.”

‘Paree Yegak’

“Paree Yegak” (PAH-ree YE-gek) means “Welcome” and should be said to guests. My aunt Mary Mirijanian Trainor cross-stitched these words for our family on linen, and her elegant creation hangs over our dining room table. I learned from my grandmother that snacks (“mezze”) should always close at hand, as guests could arrive anytime.

Last weekend, our local diaspora of Armenians welcomed guests at Leominster Library to observe the fourth annual “Armenian Remembrance Day Event.” I will write more details next week about this heart-filling event, but want to focus on the food, since you, the reader, might be asking, “what is Armenian food anyway?”

The meals my grandmother made for my grandfather always started with a platter of dried fruits, nuts, and usually grapes with cheese on “cracker bread” (“dan hatz,” in Armenian, literally “house bread”). For “Armenian Remembrance Day” we created small cups of “mezze” for our guests to eat while presenters told family stories, discussed the language (unique among the “Indo European” language tree), and read poems.

I like snacking on these foods as well — especially when on deadline (literally this very minute!). Nuts give you protein, dried fruit just enough natural sugar to keep you moving forward!

TAG GOES HERE

Armenian-style snacks

INGREDIENTS:

1 package figs

1 package dates (pitted, if you can find)

1 package apricots

1 package pistachios

DIRECTIONS:

Take a 6 oz. clear plastic wine cup, or clear glass ramekin. Put two tablespoons of pistachios in the bottom, add a layer of apricots, then two figs and a date. Serve with a napkin, as dates can be sticky!

Notes: Small bunches of grapes, string cheese with “Ak-Mak” crackers or “Crackerbread” (Leominster Market Basket carries), will fill out your tray. By offering a cup to every guest, the “handling” is minimized. Serve with a small cup of pomegranate juice, herbal tea, or very strong coffee.

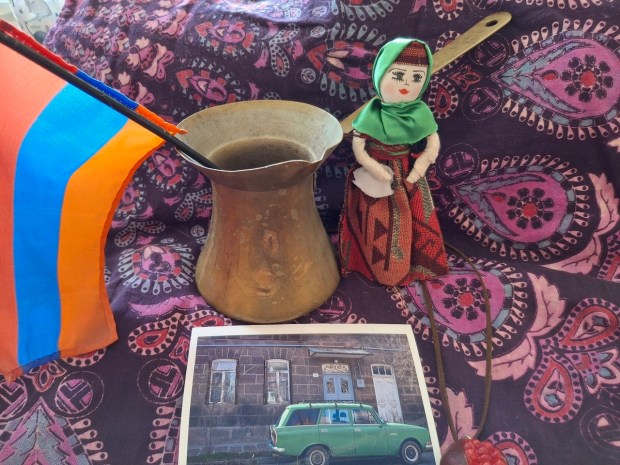

Armenian-style coffee

INGREDIENTS:

2 scoop finely ground coffee

2 tablespoon sugar — add sugar to taste

12 oz. water

DIRECTIONS:

Whisk coffee and sugar together in a very small saucepan or a brass “sourjamon” (see photo) over medium heat. When it comes to the boil, remove the container from heat. Let it boil a second time, and skim the coffee foam from the top. Put that in two cups, and slowly pour the coffee in the cup on the side, so the foam stays bubbly.

Notes: You always want to drink this style of coffee with an Armenian friend, especially one who can “read the grounds.” When you have finished drinking your coffee, quickly turn the cup over on a saucer, and let the dregs drip down. After a few minutes, lift up your cup, and interpret the designs! Peaks are mountains — flowing bits could be “travel over water”!

Next week: How to cook Armenian comfort food, and why it is impossible for Armenian people to say “good-bye.”