Kumquats are adorable, small, oval citrus fruits that you can pop in your mouth like grapes and eat whole, but the only person I ever knew to actually eat them was my father. Every Friday after work as a Florida State Park ranger, he stopped at local fruit stands to buy bags of clementines, tangerines, peaches, pecans, and a giant grocery bag filled with discount kumquats. My brother and I rushed him as soon as he walked in the door, vying for the sweet fruit. Dad kept the kumquats for himself: My mom, brother, and I couldn’t tolerate the bitter rinds. “I’m the only one in the house who won’t get scurvy,” Dad said, chewing through a handful of kumquats.

When my parents bought their first house, my father planted a kumquat tree in the front yard. Most of our neighbors and relatives had at least one on their property, as they are known for being easier to grow than other citrus fruits. When we visited my mamaw’s house for holidays, Dad filled his pockets with fruit from her tiny, decorative tree, shaking his head at the untouched, fallen kumquats below. Mamaw only used them a couple times per year, to make candied rinds for her holiday treats, jam, and kumquat pie

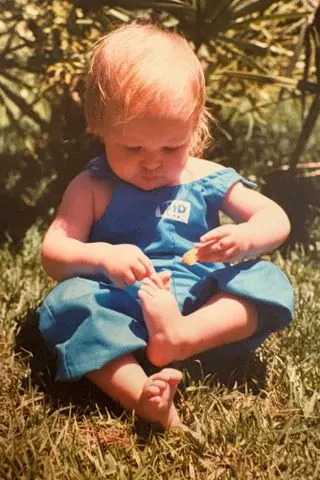

Asha Dore

Writer Asha Dore eating kumquats as a baby

I left Florida when I turned 18, and I forgot about kumquats entirely until 2015 when I saw a special at Whole Foods in Portland, Oregon. A handful of kumquats in a clamshell was offered as a superfood and “discounted” at $7. The grocery bag of kumquats my dad brought home every Friday cost one dollar, if that.

What had happened to the kumquat of my childhood is called food gentrification—when heritage foods from often-marginalized communities are rebranded as exotic and priced up. That seven-dollar “sale” price at Whole Foods told the tale: The kumquat had been inexpensive and widely available throughout its migration from South, East, and Southeast Asia to the U.S. by the late 1800s. Kumquats first appeared in Florida in landscape catalogs, described as “unusual” but pretty. Eventually, the town of Dade City in the hills west of Orlando would become a farming center for the fruit, with its nearby community of Saint Joseph dubbing itself the “Kumquat Capital of the World.” (Dade City launched an annual Kumquat Festival in 1997—it’s still going strong.)

Asha Dore

Writer Asha Dore’s Mamaw in her front yard

Traditionally, Gulf South communities primarily used the fruit in preserves, but by the early 2000s, its gentrification rocketed when it was rebranded as a gourmet fruit and superfood due to its high levels of vitamin C. Because they are cute, bright, and aesthetically pleasing, kumquats also began starring in social media posts by upscale restaurants and food influencers in New York and California.

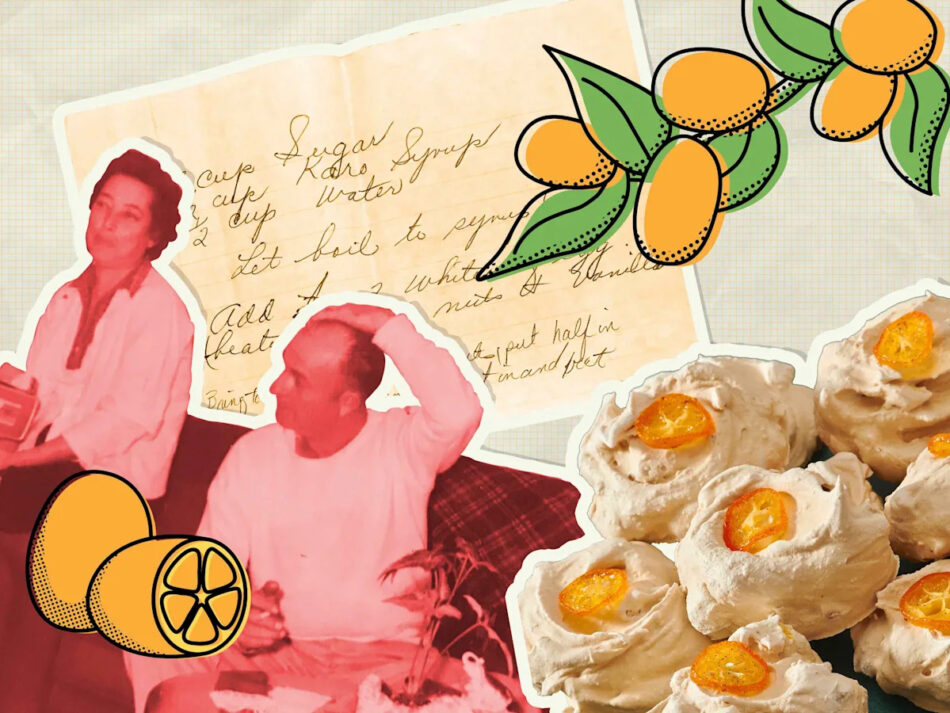

While it’s been a bit dizzying to accept the humble citrus of my Florida childhood as a luxury item, I’ve found a way to re-embrace it through my Mamaw’s holiday recipes, especially a pillowy, sweet candied kumquat divinity or creamy kumquat pie that she made during the warm, winter holidays, and preserves she made year-round. I’ve also used candied kumquats and their syrup in cocktail recipes—with or without booze. From my Pacific Northwest home, I’ve worked to source the kumquats more ethically. A chef friend offered counsel: “Start with the farmers markets,” she said. “If they aren’t available there because of the climate and growth zones, try to find local Asian or Latinx markets. At the very least, be considerate about who will benefit from your purchase.” In a world of food gentrification, this was sound advice. I might not be able to grab a big, cheap bagful of kumquats from a local fruit stand like my dad did, but at least I could connect the fruit—and my cooking—to communities that mattered and deserved to benefit.

And then there’s always fighting off scurvy. Thanks, Dad.

Allrecipes / Diana Chistruga

Mamaw’s Candied Kumquat Divinity

Divinity is traditionally made with pecans, but for this recipe, I used hazelnuts and candied kumquats.

Yield: 12-24 divinity candies, depending on size

For the Candied Kumquats:

Ingredients

-

whole vanilla bean (Optional)

Directions

-

Thinly slice kumquats, discarding ends. Remove seeds (optional).

-

Slice the vanilla bean lengthwise and scrape out the seeds.

-

Add vanilla bean seeds, sugar, honey, and water to a saucepan and bring to a boil, stirring to dissolve sugar.

-

Add kumquats to mixture and press down so they are fully submerged. Simmer for 3 minutes, then strain. You can save the liquid to add to ice cream and other dessert toppings.

-

Let kumquats sit for at least 20 minutes.

-

Reserve several candied kumquat slices for garnish. Chop remaining candied kumquats into small pieces. Set aside.

For the Divinity:

The least expensive and easiest way to make divinity includes corn syrup. This recipe gives another option.

Ingredients

-

2/3 cup roasted hazelnut pieces

-

2 tablespoons bourbon vanilla extract

Directions

-

Combine the sugar, water, and salt in a large saucepan over low to medium heat. Stir and slowly heat until sugar and salt have dissolved.

-

When mixture starts to simmer, clip candy thermometer to edge of saucepan and heat without stirring until mixture is 260 degrees F (125 degrees C).

-

While the mixture is heating, beat egg whites until stiff.

-

When the sugar mixture reaches 260 degrees F (125 degrees C), pour it in a slow stream into the egg whites, mixing at high speed. The mixture will slowly lose its gloss.

-

When it has lost its gloss and holds its shape, stop mixing.

-

Mix in the hazelnuts, vanilla, and candied kumquats.

-

Drop spoonfuls of the mixture onto a cookie sheet lined with wax paper.

-

Garnish the tops with candied kumquat slices.

You can test the mixture’s ability to hold its shape by dropping a spoonful onto a sheet of wax paper.

It helps to oil your spoon before scooping up spoonfuls and placing them on wax paper.

Once it cools, the divinity can be stored in zip-top bags.

Read the original article on Allrecipes