The following is an adapted version of an article written by Mátyás Bíró, originally published in Hungarian in Magyar Krónika.

We Hungarians have several foods and beverages whose exact recipes and methods of preparation are known only to a select few.

At the end of 2022, newspapers across the country reported that KFC’s closely guarded fried chicken recipe had been leaked, which, according to the original report, contained 11 spices, ranging from basil to celery salt. It was allegedly found in a notebook obtained by a Chicago Tribune reporter from one of the founders’ nephews. The company, of course, immediately denied the allegations. The Coca-Cola recipe is perhaps even more mysterious than that of the KFC chicken, which is why many people were surprised in 2011 when the This American Life website claimed that a photograph had been found in a 1979 issue of an Atlanta newspaper showing the exact recipe for the soft drink on an open page of a book.

The newspaper also reported that the original recipe, created by John Pemberton in 1886, is kept in a safe in Atlanta and guarded around the clock. What’s more, only two people at any given time know the ingredients of Coca-Cola. According to the leaked recipe, the ingredients include vanilla, cinnamon, coriander, nutmeg, lime, caramel, orange oil, lemon oil, walnut oil, citric acid, caffeine, and sugar. In this case, too, the news was followed by denial. This immediately raises the question: Could the companies have anything to do with such sensational cases? Do they benefit or suffer from them? It is difficult to say for sure, but the global news tsunami is rather likely to have a positive effect.

The Unicum Recipe Smuggled to the West

Here in Hungary, there are many popular foods, drinks, herbal preparations, and even sweets that have been shrouded in secrecy for decades or even centuries. Examples include certain herbal liqueurs, too, which were once primarily produced by monks. In the 1735 recipe collection of Elek Reisch, a Benedictine monk from Pannonhalma, we can find not only teas but also digestives, and liqueurs containing herbal extracts from Pannonhalma are still made based on this recipe today. In one of his writings, Abbot T Cirill Hortobágyi states that Elek Reisch’s legacy is the most valuable of all books on this subject.

The Bavarian-born trained pharmacist left us more than 500 recipes in his handwritten book entitled Praescriptiones Medicae (medical prescriptions). Today’s Pannonhalma tea bags, including liver-protecting and heart-calming blends, are still made according to his recipes, as is the balm called Arcanum (miracle cure, mysterious elixir), which contains 17 different herbs.

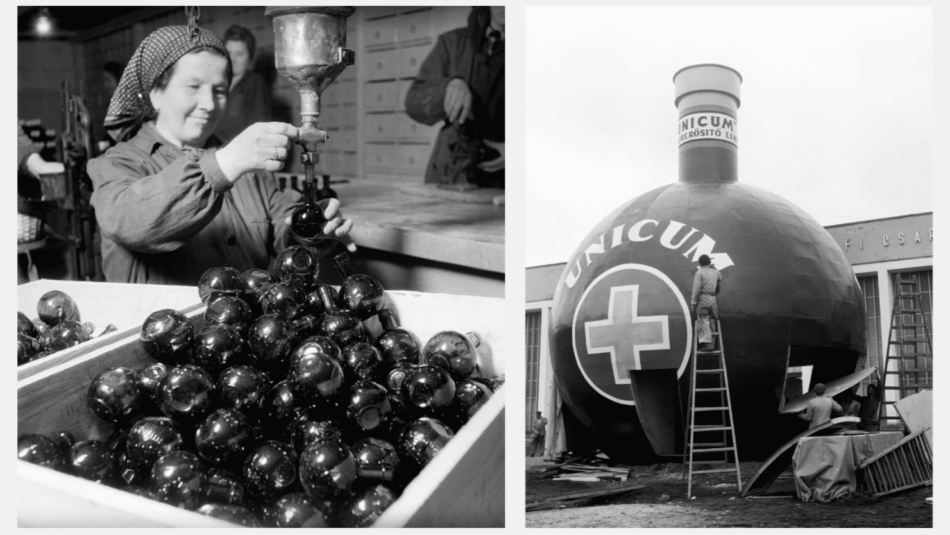

Let’s stay with herbal-based domestic drinks. Zwack’s Unicum probably needs no introduction in Hungary, and it is one of the best-known Hungarian brands worldwide. Since 1790 it has been made from 40 different spices and herbs sourced from Hungary and other parts of the world, and aged for six months in oak barrels in the cellar beneath the factory on Soroksári Road, according to the company’s website. The website also states that certain ingredients may only be added by members of the Zwack family. The trademark was registered in 1883. Interestingly, at that time, Unicum was also sold as a remedy for cholera.

The family naturally used every legal means at their disposal to protect the company’s trademarked drink. In the 13 February 1904 issue of Pesti Napló, we can read the following announcement entitled ‘Protest!’: ‘On the 8th of this month, based on our complaint, the criminal court took action against 19 beverage vendors and found other products in some of our legally protected Unicum bottles, and all kinds of products with the Unicum label in others. We will take strict action against such retailers (cafés, bars, etc)…We ask consumers to only accept Unicum in its original Unicum bottles (dark green with a red cross).’ The legal battle against counterfeiters lasted for decades, which also indicates the popularity of the drink. Even in an issue of Délmagyarország from the 1930s, we can find similar reports of abuse.

‘Today, only the company’s CEO, Sándor Zwack, his sister Izabella, who is also a member of the board of directors, and their mother know the recipe’

The family members kept the secret safe even amid historical upheavals. In 1944 János Zwack bribed the driver of a Soviet military truck and left the country under an oil barrel, with nothing in his pocket but the closely guarded recipe for Unicum. In the late 1950s János filed a lawsuit against the American distributor and the communist Hungarian state to regain the family trademark. He was successful—the state-owned company was no longer allowed to use the name of the company or the product in the West. Meanwhile, his brother Béla remained at home, working as a labourer in the former family business, supervising production, and he too did not reveal the recipe. He and his wife were soon interned in the countryside. During the socialist era, a drink that only resembled the real Unicum was produced based on a fake recipe.

The Zwacks have been guarding the ingredients and production method of Unicum for six generations. Today, only the company’s CEO, Sándor Zwack, his sister Izabella, who is also a member of the board of directors, and their mother know the recipe. Code numbers are used during production, and larger quantities of some ingredients are ordered, so the proportions cannot be revealed either.

Mysterious Liqueurs Across Europe

Chartreuse French herbal liqueur is the only one that is still produced by Carthusian monks using traditional methods, with a secret recipe containing 130 spices and herbs. Its history dates back to the 11th century. Even Napoleon wanted to obtain the secret of its production, but he did not succeed. The history of Jägermeister began in Wolfenbüttel, Lower Saxony: Curt Mast created the recipe for the herbal liqueur consisting of 56 plants in 1934. In the Czech Republic, the world-famous Becherovka is still made according to a secret recipe from the early 19th century.

The Salami-Maturing Air of Szeged

In the 1980s, winter salami was part of our festive meals. No exaggeration: children of the era hardly dared to touch it, eating it in tiny bites so that the experience would last as long as possible. Winter salami had a certain magic, and we were very grateful to our parents for allowing us to taste such a premium-quality and expensive delicacy.

Pick winter salami has been made according to a recipe invented by Márk Pick, a produce merchant, since the factory was founded in 1869, and the recipe has been kept secret ever since. Its uniqueness is largely because the production process is supervised by the salami master, who is the only person who knows the secret. It can only be made from large pigs bred in accordance with the specifications, and the meat is cut instead of minced. Then comes the real magic: the addition of secret spices. The smoking process is also unusual: it takes place over two weeks on the embers of beech wood that has been dried for a year. Finally, after 100 days of maturation, the snow-white noble mould that has become the trademark of winter salami develops. According to the manufacturer, the constant cool air of the Tisza River is also necessary for the special flavour, so the favourable microclimate of Szeged plays a major role in the maturing process.

To ‘solve’ at least one mystery surrounding the Hungarian winter salami that has been around since 2014: its name does not come from the noble mould that resembles snow, but from the fact that in the past it could only be produced in winter, as it could only be cooled with ice.

Of course, attempts have been made to imitate winter salami in the past, and they still continue to be made today, with less than stellar results. In 1929 Mátyás Kovacsics, who ran the gastronomy column of Új Idők, revealed his considerable self-confidence in an article that concluded with these amusing lines after a lengthy description of a homemade salami recipe: ‘We would like to note that if Your Excellency is not in such a hurry to obtain a recipe for winter salami, that is, if you would like something like the world-famous Dozzi or Pick, or Hertz, then please be patient, because it is more than likely that we will be able to obtain the original recipe and then perhaps send it to you by mail.’

Eagle and Lamb on the Dobos Cake

The recipe for one of the most delicious cakes was a mystery for a long time. Its creator, master chef and confectioner József Dobos, did not reveal the list of ingredients or the method of preparation for 22 years. For a long time, he placed advertisements in newspapers stating that all original Dobos cakes bear the eagle and lamb trademark, which distinguishes them from imitations. He also listed the domestic and foreign stores where the real cake is available.

He created the cake that made him world famous in 1884, but it was only presented to the general public a year later at the first National Exhibition in Budapest, held in the City Park, where Queen Elizabeth and Franz Joseph also tasted it. Before his retirement in 1906, József Dobos himself handed over the original recipe to the Association of Hungarian Confectionery Manufacturers. Although the secret became known, the complicated production process and the difficulty of obtaining some of the ingredients mean that even today, it takes a great amount of determination, courage, and patience to make a genuine Dobos cake.

The World’s Most Secret Cakes

The Monastery of Saint Jerome is located in Belém, a district of Lisbon. In the 1800s, monasteries were closed in Portugal, and the monks of Belém chose confectionery as their new vocation. Their main product became the Pastel de Belém, a delicious, creamy pastry made according to an old recipe. It is only available there—20,000 pastries are baked every day, all by hand. The recipe is so secret that only four people know it.

And one more mysterious cake to finish with. There was a pleasant place on Lövőház Street in the early 2010s, the Karády Katalin Museum Café, whose menu featured a delicacy made according to a secret recipe, the Karády cake. After the actress moved to New York, she ate this cake every Sunday, made by an Italian pastry chef. At home, although several pastry chefs tried to decipher the recipe, they were unable to reproduce the dessert perfectly. What is fairly certain is that it was based on Sacher cake, but the secret ingredient that gave it its special flavour has never been revealed. And perhaps it never will be.

Read our previous articles about famous Hungarikums:

Click here to read the original article.